Data as of: December 7, 2025

Contents

I. Research Summary

- Key Takeaways

- As a foundational pillar of the global digital economy, Alphabet (Google) benefits from its dominant position in search and advertising, which underpins an exceptionally strong cash flow–generation capability. As of 2025, its core businesses continue to deliver stable growth, with operating margins steadily expanding into the 30%+ range.

- AI-driven cloud computing has emerged as a critical second growth curve. In Q3 2025, Google Cloud accounted for 15% of total revenue, with 34% year-over-year growth, marking a return to a high-growth trajectory. Profitability has also continued to improve, with margins rising from 17% in the prior-year period to 24%, and further upside potential remains.

- The explosive development of the AI industry and its rapid penetration into global user markets have created complex and far-reaching implications for Alphabet, characterized by both opportunities and challenges:

- In the short term, the rapid advancement of AI has not yet posed a material threat to Alphabet’s core business—search advertising. On the contrary, Google has leveraged AI capabilities to enhance conversion efficiency in search advertising. The rollout of AI Overviews has helped stabilize Google’s search user base. Based on current advertising revenue trends and management-disclosed ROI data, there is no clear evidence of a meaningful decline in search conversion rates or ad unit value. Instead, AI adoption has demonstrably improved operational efficiency across multiple internal product lines.

- In the medium to long term, however, Q&A-style AI represents a genuine structural threat to Alphabet’s business model. User search behavior has already begun migrating toward AI-native products. While Google’s AI Overviews may temporarily slow user attrition, the competitive, multi-player AI landscape is difficult to reverse. Replicating Google’s historical monopoly in traditional search within the AI domain remains challenging. Even if Google were to maintain a dominant position in AI search, the higher unit costs and reduced advertising inventory inherent to AI-driven search experiences would likely compress advertising margins.

- At the same time, Google’s powerful product ecosystem provides a meaningful advantage in the AI era. Unlike AI-native players such as GPT or Claude, which must independently acquire and retain users, Google can efficiently distribute Gemini and other AI tools through its extensive product matrix—Search, Chrome, YouTube, Gmail, Maps, Android, and enterprise offerings. In the forthcoming wave of AI Agents, Google is well positioned to embed AI deeply across consumer and enterprise workflows. This embedded presence is expected to generate massive data feedback loops, enabling continuous improvement of underlying models and ultimately forming a stronger, more comprehensive moat than that of the traditional internet era.

- Alphabet’s TPU-based AI accelerator portfolio has begun to serve as both an internal and external substitute for NVIDIA’s GPU offerings. Coupled with recent purchases by Berkshire Hathaway, market narratives have turned increasingly optimistic—framing Google as owning the most complete AI value chain and capable of “one-versus-many” competition—thereby driving a rapid valuation recovery. In reality, NVIDIA’s core business remains highly resilient, with AI infrastructure products still facing supply constraints in the near term. Both companies are currently in a phase of expanding the overall market, though over the medium term, TPUs are likely to capture a portion of NVIDIA’s market share.

- Market warnings regarding a potential “AI bubble” are primarily centered on three concerns: 1. elevated corporate valuations and increased market-cap concentration; 2. excessive capital expenditures that may be difficult to justify with sustainable downstream, long-term revenues; 3. financial accounting concerns, including extended depreciation timelines and supplier-financing arrangements. In our view, market concerns related to the third point are overstated and likely to have a limited practical impact. Valuation levels under the first point remain well below those observed during the 2000 dot-com bubble. The most critical issue lies in the second point, namely the extent of genuine downstream demand, which, at present, appears relatively robust. Even in the event of an AI bubble correction, representative companies such as Google, supported by highly resilient core businesses that account for the majority of revenue and profit contributions, should be capable of absorbing and smoothing the impact, making a repeat of the 70%+ collapse seen in 2000 unlikely.

- The breakup risk stemming from the 2024 U.S. federal antitrust ruling was largely resolved in the September 2025 federal court decision. The final outcome proved limited in its impact on Alphabet, with no mandated divestitures of Android or Chrome, representing the most favorable scenario previously anticipated. However, European antitrust actions continue to emerge, involving recurring multi-billion-dollar fines and a range of ongoing investigations. Most recently, on December 9, the European Union initiated a new antitrust investigation into Google’s AI-related practices.

- Valuation Assessment

At present, Alphabet can be characterized as a high-quality asset trading at a reasonable but slightly premium valuation. Current pricing already reflects expectations of a second growth curve driven by AI-enabled cloud expansion, yet it has not entered a severe bubble territory where valuations are entirely disconnected from fundamentals. If one holds a sufficiently optimistic view on downstream AI demand and believes that Alphabet’s medium- to long-term profit and free cash flow growth can be sustained at low double-digit levels (above ~12%), the current valuation remains acceptable, albeit requiring time for multiple digestion. Conversely, under a more conservative outlook on AI monetization and the regulatory environment, Alphabet should be viewed as a high-quality, long-term holding that is not cheap at current levels, rather than a clearly undervalued, high-conviction overweight opportunity.

- Potential Catalysts and Risks

Catalysts:

- Full-scale commercialization of the Gemini model suite.

- Continued expansion of cloud operating margins toward AWS/Azure benchmarks;

- Sustained acceleration in downstream AI demand;

- Securing additional landmark contracts for TPU cluster services.

Risks:

- Intensifying industry competition with no clear winner yet, alongside the proliferation of open-source AI models, which may commoditize AI computing power.

- Tightening global regulation and antitrust scrutiny, particularly breakup-related risks;

- Excessive AI-related capital expenditures are weighing on profitability.

- Slower-than-expected growth or insufficient scale in downstream AI demand;

- A broader macroeconomic slowdown.

II. Company History

Before examining the industry landscape and Alphabet’s specific business lines, it is necessary to review Google’s historical development. From this history, we can distill how the company’s trajectory has been shaped by the founders’ personal characteristics and its overall strategic orientation.

Phase I: Early Formation and the Establishment of Search Dominance (1996–2003)

This phase marked the critical period during which Google established its core technologies and its foundational commercial model—advertising—while also forming the long-standing “triumvirate” management structure.

- 1996: Larry Page and Sergey Brin developed the search engine BackRub at Stanford University, which would later become the predecessor to Google.

- September 1998: Google was formally incorporated. Its first external funding came from Andy Bechtolsheim, co-founder of Sun Microsystems, in the amount of USD 100,000. The company operated out of the garage of Susan Wojcicki, an early Google employee and later former CEO of YouTube (now deceased).

- 1999: Google raised USD 25 million in funding from Sequoia Capital and Kleiner Perkins (KPCB) and relocated its offices to Mountain View, California.

- 2000: Google launched AdWords, laying the cornerstone of its commercial empire. The platform allowed advertisers to purchase search keywords, formally establishing Google’s search-based monetization model. During this period, the company also articulated its well-known informal motto: “Don’t be evil.”

- August 2001: Page and Brin recognized the need for an experienced professional manager. Eric Schmidt was appointed CEO, giving rise to the “triumvirate” leadership structure that would define Google’s governance for the following decade.

The so-called “triumvirate” refers to the internal power triangle that existed during Schmidt’s tenure, composed of:

- Eric Schmidt — Chairman and CEO, acting as both the company’s “parental figure” and “diplomat.” He was responsible for all external-facing matters, including Wall Street and investor relations, government and regulatory engagement, sales organization development, legal affairs, and day-to-day operations.

- Larry Page — Co-founder and product leader, focused on Google’s core products, including search, advertising, and long-term visionary initiatives. Page was known for his near-obsessive emphasis on user experience, speed, and efficiency. However, due to his limited interest in social interaction and managerial details, early investors viewed him as ill-suited for the CEO role—one he would later ultimately assume.

- Sergey Brin — Co-founder and chief technology visionary, responsible for recruiting top-tier talent, preserving Google’s distinctive engineering culture, and exploring “moonshot” projects beyond the core business, such as what would later become Google Brain and the company’s AI initiatives.

Under this structure, responsibilities were clearly divided, but major strategic decisions required consensus among all three leaders. Schmidt once joked that his job was simply “to decide who was right when Larry and Sergey were arguing.”

Phase II: IPO, Acquisitions, and Ecosystem Expansion (2004–2010)

During this period, Google secured substantial capital through its IPO and cemented its dominance in the mobile internet era through a series of highly consequential acquisitions and strategic decisions. These moves laid the foundation for the company’s enduring advertising traffic moat.

- April 2004: Launch of Gmail, which stunned the industry with an unprecedented 1 GB of free storage.

- August 2004: Google went public on NASDAQ. The company adopted a dual-class share structure, with Page, Brin, and Schmidt holding Class B shares with super-voting rights.

- 2005: Google quietly acquired Android for approximately USD 50 million. This proved to be one of the highest-return acquisitions in the company’s history, providing a critical strategic foundation for competition in the mobile era. Android became Google’s primary platform for mobile advertising, app distribution, and data collection, securing a core position within the smartphone industry value chain. In the same year, Google launched Google Maps, a foundational infrastructure product that would later become the geographic backbone for a wide range of mobile-era applications.

- October 2006: Google acquired YouTube for USD 1.65 billion, establishing its dominant position in online video streaming.

- September 2008: Launch of the Chrome browser and the first Android smartphone (T-Mobile G1). Google formally entered the operating system and browser markets, completing the formation of a tightly integrated and highly synergistic core ecosystem—one that has largely persisted to this day.

- January / March 2010: Google exited the mainland China market.

Phase III: Mobile-First Strategy, Reorganization, and the Shadow of Antitrust (2011–2018)

With Schmidt stepping aside, Page’s return and Sundar Pichai’s eventual rise marked a period of profound structural change at Google, alongside mounting global regulatory pressure.

- April 2011: Larry Page resumed the role of CEO, while Eric Schmidt transitioned to Executive Chairman. Page initiated a streamlining of the product portfolio—shutting down services such as Google Reader—and refocused the company on its core businesses.

*The background to Schmidt’s transfer of authority was multifaceted: rapid headcount growth led to early signs of “big-company disease”; Facebook’s rapid ascent in 2010–2011 diverted user attention toward social networks, to which Schmidt responded too slowly; and after more than a decade of experience, Page had matured as a leader and long harbored the ambition to take full control of Google.

- 2013: As the business continued to scale, Google began developing TPUs internally to reduce computing costs. The first-generation product (TPU v1) was deployed and put into internal production use in 2015.

- 2014: Acquisition of DeepMind, the UK-based AI lab that later developed AlphaGo, which shocked the world and became a central engine of Google’s subsequent AI strategy.

- August 2015: A landmark corporate reorganization led to the formation of Alphabet Inc.

- Governance restructuring: Google became a wholly owned subsidiary of Alphabet. The objective was to separate the core internet businesses (Search, YouTube, Android) from “moonshot” initiatives (Waymo autonomous driving, Verily life sciences, among others), thereby improving financial transparency and enhancing valuation.

- Leadership changes: Larry Page assumed the role of CEO of Alphabet, Sergey Brin became President, and Sundar Pichai, a former advertising plug-in product manager, was promoted to CEO of Google.

- Beyond improving financial transparency and creating space for Pichai’s ascent, the establishment of Alphabet also reflected broader strategic considerations: protecting innovation (by separating experimental businesses from mature operations to avoid budgetary and KPI interference), and isolating legal and brand risks (allowing risks associated with autonomous driving and other ventures, such as Waymo, to be ring-fenced from the core Google brand).

- 2016: Google announced a strategic shift from “mobile-first” to “AI-first.” The company launched Google Assistant and the Pixel smartphone lineup. In May, at its Google I/O developer conference, Google publicly disclosed the existence of TPUs for the first time, revealing its custom ASIC chips designed for deep learning. Beginning in 2018, TPUs were made available externally through Google’s cloud services.

- 2017: Google Brain published “Attention Is All You Need,” the landmark paper introducing the Transformer architecture.

- 2017–2019: A series of three major antitrust actions by the European Union. The European Commission fined Google a cumulative over EUR 8 billion for anticompetitive practices related to Google Shopping, Android app bundling, and AdSense advertising dominance. These cases marked the beginning of a prolonged and persistent wave of antitrust litigation from the EU.

Phase IV: The Post-Founder Era and the AI Arms Race (2019–2024)

With the founders fully stepping back and Sundar Pichai assuming consolidated control, Google entered a period defined by intensifying competition from OpenAI, an internal shift to wartime footing on AI, and the most severe antitrust challenges in its history within the United States.

- December 2019: Larry Page and Sergey Brin stepped down as CEO and President of Alphabet, respectively. Sundar Pichai assumed the dual role of CEO of both Alphabet and Google. While the founders continued to exercise control through board influence and voting rights, they withdrew from day-to-day management. Their retreat reflected not only confidence in Pichai’s leadership, but also fatigue with escalating congressional scrutiny and internal controversies, including employee protests (such as the departure of Android founder Andy Rubin following sexual misconduct allegations while receiving a USD 90 million exit package, and Google’s involvement in military-related projects).

- October 2020: The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) filed a landmark antitrust lawsuit, alleging that Google maintained an illegal monopoly in search and search advertising, including practices such as paying Apple billions of dollars annually to remain the default search engine.

- November–December 2022: The release of ChatGPT triggered an internal crisis response. Pichai issued a “Code Red” alert, viewing the company’s core search business as facing its most significant existential threat since inception. He urgently contacted Page and Brin, both of whom returned multiple times to Google’s Mountain View headquarters to participate in high-level strategy reviews of the company’s AI product roadmap. Sergey Brin, in particular, chose to return directly to frontline work, taking up regular office presence at Google’s newly completed AI headquarters, the Charleston East building. According to employee accounts, Brin became deeply involved in Gemini’s technical reviews, personally intervened to retain key AI talent, and even contributed code directly. Subsequent developments suggest that Google’s accelerated progress in AI owed much to Brin’s timely return.

- January 2023: A historic round of layoffs was announced, affecting approximately 12,000 employees (around 6% of the workforce). This marked the end of Google’s long-standing reputation for job security and generous benefits, and caused significant internal morale disruption.

- January 2023: The DOJ filed a second major antitrust lawsuit, this time targeting Google’s digital advertising technology (AdTech) business.

- February–December 2023: The AI counteroffensive. Google’s rushed launch of Bard (later rebranded as Gemini) was met with widespread criticism. In response, Google merged Google Brain and DeepMind to form Google DeepMind, led by Demis Hassabis (founder of DeepMind and recipient of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry), with the explicit aim of accelerating AI research and development.

- August 2024: A landmark ruling by a U.S. The federal judge found Google to be an illegal monopolist in search services and general text advertising. This represented the most significant antitrust defeat for a U.S. technology company since the Microsoft case, raising the possibility that Google could be prohibited from paying Apple and other partners for default search placement, and even face potential breakup risks.

Phase V: Regulatory Resolution and Technological Revival (2024–2025)

From being ruled a monopolist by a federal court to the implementation of a “light-touch” remedy, and from being perceived as an AI-era laggard to regaining product credibility and returning to the top tier of AI leadership with the release of Gemini 3.0, Alphabet’s past year has been marked by dramatic reversals.

- May 2024: AI Overviews took over search. Despite early controversy—particularly around hallucination issues—Google persisted in placing AI-generated answers above traditional blue links, initiating a structural shift from information retrieval to question-and-answer within its ecosystem products.

- September 2025: The U.S. The federal court issued its final ruling. While imposing several restrictions unfavorable to Google, including:

- prohibiting certain exclusive agreements that bundled search distribution (such as arrangements with device manufacturers or browsers requiring exclusive pre-installation of Google Search);

- requiring Google to share a defined scope of search index and user interaction data with competitors to lower entry barriers for new search services;

- banning exclusive promotion arrangements for Gemini, Google Assistant, and other emerging AI entry points, to prevent Google from replicating its historical monopoly path in the AI search era;

- the court rejected the DOJ’s request to mandate the divestiture or sale of Chrome or Android, and did not restrict Google’s ability to pay Apple, Samsung, and other handset manufacturers to remain the default search engine. By preserving Google’s primary sources of search traffic, this outcome represented the most favorable realistic ruling for the company.

- October 2024: Leadership transition in search. Longtime head of Google’s core search and advertising business, Prabhakar Raghavan, stepped down and transitioned into the role of CTO, with Nick Fox assuming leadership. This move was widely viewed as a strategic deployment by Pichai to accelerate the triadic integration of “AI + Assistant + Search,” break down internal silos, and fully advance Google’s AI Agent strategy.

- November 2025: Gemini 3.0 reclaimed the crown. After a year of rapid catch-up, the release of Gemini 3.0 marked a comprehensive outperformance of rival GPT-5 in complex logical reasoning and native multimodal understanding, including the ability to directly interpret video streams. The model even received public praise from competitors’ founders, including Sam Altman and Elon Musk, reestablishing Google’s leadership in foundation models and largely dispelling capital-market concerns that Google had fallen behind in the AI era.

- Full-year 2025: The advantages of TPU-based compute became increasingly evident. Against a backdrop of tight and costly NVIDIA GPU supply, Google’s self-developed TPU v6 (Trillium) emerged as a decisive advantage, outperforming competing products in both overall efficiency and unit cost. Beyond internal use, major players such as Apple Intelligence and Anthropic adopted Google TPU clusters for core model training, generating substantial cloud revenue and strong third-party validation. Google is also reportedly in discussions with Meta regarding multi-billion-dollar TPU procurement agreements.

Summary

Looking back over three decades of Google’s evolution, the two founders instilled a cultural core centered on innovation and the principle of “Don’t be evil,” once serving as the highest beacon of Silicon Valley’s engineering ethos. During its first 15 years, Google made a series of critically correct strategic decisions, building a remarkably wide competitive moat. However, as the company scaled and the founders gradually stepped away, structural challenges began to surface: diminished product sensitivity, declining organizational efficiency, growing cultural divergence, difficulties in translating foundational research into engineering and products, and a sharp rise in antitrust risk. Google’s midlife crisis has only just begun. Although its AI products have regained momentum and improved market perception over the past year, the continued deepening of AI penetration among users also poses a direct threat to its core search advertising business. This issue will be examined in greater detail in subsequent sections.

III. Business and Industry Overview

Alphabet operates across a broad range of businesses, including digital advertising, cloud computing, online video, consumer electronics, and autonomous driving, while attempting to use artificial intelligence as a unifying accelerator to drive growth across all segments.

This section provides a disaggregated analysis of each major business line, covering both operating metrics and industry dynamics, with particular emphasis on artificial intelligence. Although AI is not reported as a standalone business segment within Alphabet’s financial disclosures, it functions as a group-wide accelerator and, through TPU-centric AI computing services embedded within Google Cloud, represents the company’s core source of future value creation. For this reason, AI is analyzed separately in a dedicated subsection.

I would like to point out that overlaps exist among the business classifications listed below. For example, total revenue under the “Digital Advertising and Search” segment includes YouTube display advertising, yet given YouTube’s strategic importance, it is analyzed separately. Similarly, YouTube subscription revenue is also partially captured within the broader category of “Subscriptions, Platforms, and Consumer Hardware.”

3.1 Digital Advertising and Search

3.1.1 Industry Overview and Competitive Landscape

The global advertising market surpassed USD 1 trillion for the first time in 2024, with the share of digital advertising continuing to rise and expected to reach 82% of total ad spend by 2025. Leveraging Google and YouTube, Alphabet has long ranked first globally in digital advertising revenue.

However, the competitive landscape has shifted in recent years:

- Google’s market share has come under increasing pressure from major players such as Meta and Amazon.

- In search advertising, Google still commands approximately 90% of global search engine user share, but its revenue share is declining. According to eMarketer estimates, Google’s share of U.S. search advertising revenue may fall below 50% for the first time in 2025, driven by the diversification of search behavior and the rising ad share of vertical e-commerce platforms, social media, and short-video search.

- In the broader digital advertising market, Google’s share declined by approximately 7.6 percentage points from 2021 to 2025, dropping to below 50%, while Meta and Amazon increased their shares by roughly 3 and 4 percentage points, respectively.

The primary drivers behind these shifts include:

- The rise of social advertising: Meta has seen rapid growth in social ad spending driven by Instagram and Facebook, attracting an increasing share of brand marketing budgets.

- The expansion of e-commerce advertising: Amazon has leveraged its marketplace traffic to scale search and display advertising, rapidly growing its ad business.

- The emergence of short-video platforms: Platforms such as TikTok (under ByteDance) continue to capture incremental user attention and advertising budgets.

Despite intensifying competition, Alphabet retains several structural advantages in digital advertising:

- Search advertising delivers clear performance and high ROI, and remains a primary online marketing channel for most small and medium-sized businesses.

- The overall digital advertising market continues to expand—global digital ad spend grew approximately 15% YoY in 2024, and is projected to reach USD 723 billion by 2026, implying a ~9% CAGR.

3.1.2 Business Positioning and Structural Role

Alphabet’s search and advertising business primarily comprises:

- Google Search & Other: advertising across search and other owned traffic properties;

- YouTube Ads (video advertising, discussed in the following subsection);

- Google Network: partner network advertising, including AdSense, Ad Manager, and third-party websites/apps.

Together, these form the Google Ads ecosystem, which is Alphabet’s undisputed cash cow:

- Advertising accounted for approximately 78% of total group revenue in 2024.

- In Q3 2025, advertising still represented over 70% of quarterly group revenue.

3.1.3 Latest Quarterly (Q3 2025) Core Metrics and Profit Contribution

Revenue composition (quarterly):

- Total group revenue: USD 102.3 billion, +16% YoY, surpassing USD 100 billion for the first time;

- Google Services (primarily advertising + subscriptions + hardware): USD 87.1 billion, +14% YoY, with advertising broken down as follows:

- Google Search & Other: USD 56.6 billion, +15% YoY, the single largest contributor to growth;

- YouTube Ads: USD 10.3 billion, approximately +15% YoY;

- Google Network: USD 7.4 billion, –2.6% YoY, continuing a gradual contraction.

Total Google advertising revenue reached approximately USD 74.18 billion, +12.6% YoY, accounting for roughly 72% of group revenue.

Profit contribution:

- In Q3, Google Services’ operating income totaled approximately USD 33.5 billion, with an operating margin of 38.5%.

- Excluding the impact of a USD 3.5 billion EU antitrust fine, adjusted operating income was approximately USD 37.0 billion, implying a margin of 42.5%, an improvement of about 2.2 percentage points YoY;

- Over the same period, Alphabet’s consolidated operating margin was only 30.5% (33.9% adjusted).

These figures underscore that high-margin search and advertising continue to contribute the vast majority of group operating profits, while Cloud and Other Bets, although moving toward profitability or reduced losses, remain far smaller in absolute earnings contribution.

Short-term trends:

- Search and YouTube advertising have delivered double-digit growth for multiple consecutive quarters (Q2 search +12% YoY; Q3 +14–15%), demonstrating resilience despite rapid AI adoption, rising user penetration, and intensified competition among major platforms;

- The only declining segment remains Network advertising, largely due to management’s deliberate strategy to de-emphasize lower-quality partner inventory and redirect ad spend toward owned traffic and higher-quality placements.

3.1.4 Medium-Term Growth Trends and Key Drivers

High advertising share with ongoing structural adjustment:

- Advertising contributed nearly 80% of total revenue in 2024. Following single-digit growth during the macro-driven slowdown in 2022, growth reaccelerated to low double digits during 2023–2025, with Search and YouTube consistently outperforming the group average;

- Structurally, the share of owned traffic (Search + YouTube) has increased, while Network exposure has declined, enhancing overall quality and pricing power.

AI-enhanced search and advertising:

- As of 2025, AI Overviews reach over 1.5 billion monthly users, with AI Mode fully rolled out across markets, including the U.S..

- Management has repeatedly emphasized that search results with AI Overviews monetize at levels broadly comparable to traditional search.

- Following the full rollout of AI features, Search revenue continued to grow 10–12% YoY in Q1/Q2, accelerating further to +14–15% in Q3, suggesting that Google’s search ad revenue has not suffered observable negative impact from the broader adoption of AI search.

- AI Max in Search, launched globally in September 2025, has become Google’s fastest-growing AI search advertising product, unlocking billions of incremental search queries in Q3 alone and being adopted by hundreds of thousands of advertisers. The underlying logic is straightforward:

- large language models better understand long-tail and complex queries;

- previously unmonetizable demand is surfaced and matched with ads;

- the addressable market for search advertising expands.

Further improvement in profit quality:

- Alongside the return to double-digit ad growth, Google Services’ adjusted operating margin has risen to approximately 42–43%;

- Management disclosed in Q3 that both paid clicks and average CPC (cost per click) achieved mid-single-digit YoY growth, indicating advertisers’ willingness to pay for Google traffic continues to increase.

Not Yet Evident: The Long-Term Impact of AI on Intent-Based Advertising

Does the continued strength of Google’s search advertising imply that concerns over AI disrupting Google’s core ad business have been disproven and can now be dismissed?

In the author’s view, the answer is no.

To understand why rising penetration of AI products—whether general-purpose models such as GPT, AI-native search tools like Perplexity, or Google’s own offerings such as AI Overviews and Gemini—could ultimately disrupt Google’s advertising business, it is necessary to first deconstruct search advertising itself.

Google’s search advertising is often described as the “commercial intent advertising market.” “Intent” refers to the underlying objective a user seeks to achieve when acting such as searching, clicking, purchasing, or asking a question.

User search intent can broadly be categorized into four types:

- Informational: seeking knowledge (e.g., “Is milk carcinogenic?”, “How to write OKRs”);

- Navigational: finding a specific site (e.g., “Taobao”, “China Merchants Bank Credit Card Center”);

- Commercial: researching products (e.g., “best laptops for remote work”);

- Transactional: preparing to purchase (e.g., “MacBook Air M3 JD”).

The highest-ROI segments, which generate the majority of Google’s search advertising revenue, are commercial and transactional intent, with navigational intent contributing partially. Informational intent, while valuable to users, is much harder to monetize and contributes relatively little to advertising revenue.

As such, Google’s search profitability can be expressed through a simplified equation: Advertising Profit = Search Volume × Monetizable Intent Share × Ad Slots per Page × CPC × Click-Through Rate – (Search Costs + Traffic Acquisition Costs)

The increasing penetration and maturation of AI products exert varying degrees of pressure on multiple components of this equation, with the most direct impacts likely on search volume, ad inventory, and search costs.

- Declining search volume: A growing number of users are shifting from traditional Google searches to AI platforms for queries and problem-solving, reducing the top of Google’s revenue funnel—total search volume. Ask yourself: after experiencing tools such as GPT, Perplexity, DeepSeek, or Doubao, how often do you still search for information on Baidu or Google? Moreover, while products such as Gemini 3.0 have recently received strong user feedback, they are not generation-defining leaders. Gemini’s user mindshare and market share in AI products remain far from Google’s historical monopoly in traditional search. As users migrate from classic search to AI interaction, market share is effectively reshuffled, representing the largest potential disruption.

- Compression of advertising inventory: Unlike traditional search pages filled with links and multiple ad placements, AI Q&A experiences deliver more concise, intent-driven responses with limited space for advertising. In addition, GPT-style AI products function more like trusted intelligent assistants. Users expect neutrality and accountability in AI-generated answers; if recommendations appear overly driven by advertising, user trust erodes rapidly. This differs fundamentally from search engines, where users assume responsibility for filtering and interpreting information from a large pool of results.

- Significantly higher search costs: The cost of a single AI-powered search is 5–10 times higher than that of a traditional search. If AI overviews are fully rolled out, the incremental annual costs could amount to tens of billions, or even approach USD 100 billion, potentially absorbing a substantial portion of profits.

Given the visible rise in AI penetration, why have Google’s search advertising revenue and profits not only held up but continued to grow, with net margins remaining resilient despite higher search costs? In the author’s view, several factors are at play:

- Immaturity of competing ad markets: The advertising ecosystems around AI platforms—both general-purpose models such as GPT and AI-native search tools like Perplexity—have yet to launch scalable, production-ready advertising products. Core components such as auction mechanisms, attribution systems, and settlement infrastructure remain underdeveloped. Until these foundations are in place, advertisers complete large-scale experimentation, and stable ROI benchmarks are established, Google Search advertising remains the default choice, and meaningful budget reallocation has yet to begin. That said, companies led by OpenAI have already begun exploring advertising and shopping-oriented features through limited pilot programs, signaling that this dynamic may evolve over time.

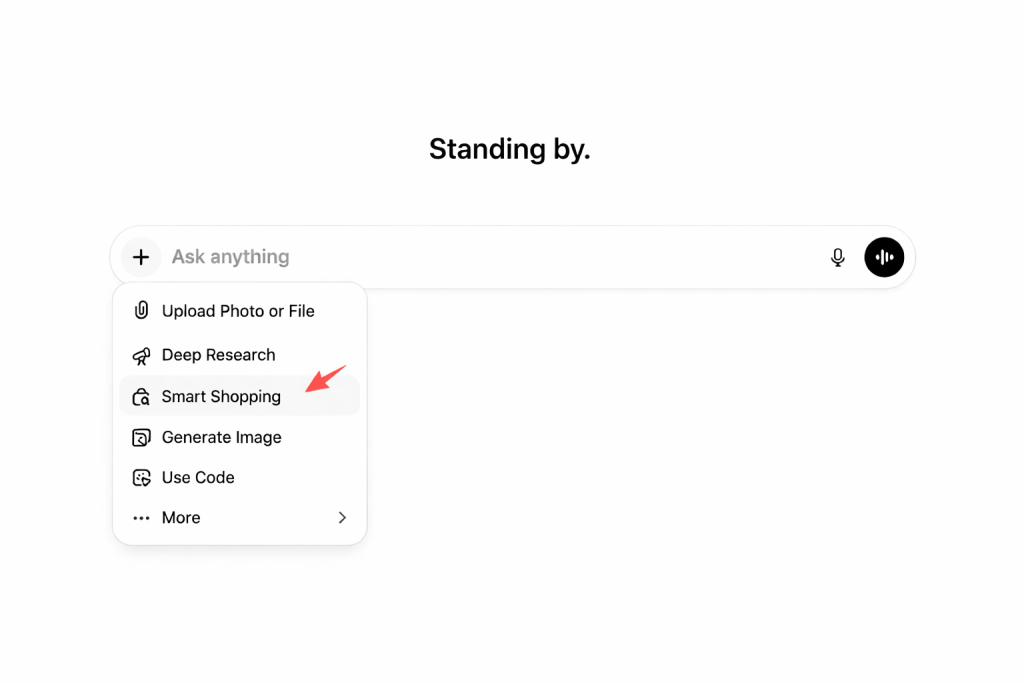

On other GPT interaction pages, pop-up prompts guiding users to shopping assistants also appear occasionally

- At present, the market is still in a transition phase where AI enhances search rather than replaces it. In other words, AI currently plays a more supportive than substitutive role relative to traditional search. For example, Google’s AI Overviews improve the search experience, increase users’ willingness to search, and help retain users. Likewise, products such as AI Max in Search expand advertisers’ spending by matching ads to a broader set of latent and long-tail demand.

- The impact on margins is being deferred. The higher unit compute costs introduced by AI Overviews do not immediately show up as higher operating expenses in current financial statements. Instead, they are transmitted through the following path: rising AI compute demand → construction of more data centers (accounted for as capital expenditures rather than operating costs) → growth in fixed assets → higher depreciation charges in subsequent years. As a result, the first area to be affected is Google’s free cash flow (which is already visible in recent financials), with profits being eroded gradually over time through depreciation. In addition, Google carried out large-scale layoffs and efficiency improvements in 2023–2024, introducing stricter cost discipline, which has materially helped support margins.

Therefore, the impact of rising AI penetration on Google’s search advertising business may not have truly manifested yet.

3.2 YouTube: Online Video and Media Entertainment Advertising

3.2.1 Industry Overview and Competitive Landscape

The online video platform industry in which YouTube operates has expanded rapidly in recent years, continuing to encroach on user time spent on traditional television and streaming media:

- As of 2025, YouTube’s monthly active users exceeded 2.7 billion, ranking second only to Facebook and reaching approximately 52% of the global internet population.

- Daily watch time exceeds 1 billion hours, driving rapid expansion of the online video advertising market, in which YouTube holds a dominant share, particularly in UGC-based short-form and mid-to-long-form video advertising.

Challenges are also intensifying:

- TikTok’s global monthly active users have reached approximately 1.59 billion and continue to grow, with short-form video advertising remaining a high-growth emerging segment.

- Streaming giants such as Netflix and Disney+ have introduced ad-supported tiers, competing with YouTube for brand advertising budgets.

- YouTube itself is actively promoting paid subscriptions (YouTube Premium, YouTube Music, etc.), with total subscribers exceeding 125 million, requiring dynamic balancing between advertising and subscription monetization.

Overall trends:

- User viewing habits continue to migrate toward online video, with video advertising expected to maintain double-digit growth.

- The evolution of content formats and intensifying competition require YouTube to continuously innovate product formats (such as Shorts) to sustain user engagement and advertiser appeal.

3.2.2 Business Positioning and Structural Role

YouTube is Alphabet’s core platform for online video and social-style media entertainment, including:

- YouTube Ads: advertising across long-form video, Shorts, live streaming, and TV (Living Room) platforms;

- Subscriptions and value-added services: YouTube Premium / Music, channel memberships, tipping, etc. (accounted for under “Google subscriptions, platforms and devices”).

From a group perspective:

- In 2024, YouTube advertising revenue reached USD 36.1 billion, up 14.6% year over year, accounting for roughly 10% of Alphabet’s total revenue;

- On the user side, monthly active users reached approximately 2.7 billion by mid-2025, second only to Facebook globally.

As a result, YouTube serves as Alphabet’s second growth engine across video, social, “TV-like” advertising, and subscriptions—both a key contributor to advertising cash flow and a strategic lever for expansion into the living room and broader entertainment markets.

3.2.3 Latest Quarterly Performance (2025 Q3): Key Metrics and Profit Contribution

Revenue and growth:

- In 2025 Q3, Alphabet reported total revenue of USD 102.3 billion, up 16% year over year;

- YouTube advertising revenue reached USD 10.3 billion, up 15% year over year, surpassing USD 10 billion in a single quarter for the first time. YouTube ads recorded approximately 15% growth in both Q2 and Q3, driven by Shorts, Living Room (TV), and the recovery of brand advertising.

Subscriptions:

- While YouTube-specific subscription revenue is not disclosed separately, management emphasized that Google subscriptions (including YouTube Premium and Google One) grew 21% year over year in Q3, making it one of the fastest-growing subsegments within Google Services.

Profit contribution:

- YouTube advertising falls under the high-margin Google Services segment, with primary costs related to revenue sharing with creators and rights holders.

- Although standalone profit figures are not disclosed, the market generally estimates YouTube’s operating margin to be slightly below search but above that of most traditional media companies.

- Based on revenue scale, YouTube (advertising plus subscriptions) now contributes close to 12–15% of Alphabet’s total revenue, with its contribution to Google Services profits rising rapidly, transitioning from a marginal increment to a core earnings pillar.

Trend-wise:

- From low-single-digit or even negative growth during the macro downturn in 2022, YouTube advertising rebounded to double-digit growth from 2024 through mid-2025, making it the second-largest revenue contributor within Alphabet after Cloud.

- This indicates that YouTube has emerged from the advertising cycle and entered a healthier phase driven by both advertising and subscriptions.

3.2.4 Medium-Term Growth Drivers and Competitive Dynamics

- Content formats: dual engines of shorts and TV

- Shorts (short-form video): In the U.S. market, advertising revenue per hour of Shorts viewing has surpassed that of long-form video, making it a key contributor to Q3’s 15% ad growth;

- Living Room (TV): Watch time on large-screen TVs continues to rise, with interactive performance advertising on TV exceeding USD 1 billion in annualized revenue. YouTube has effectively entered the TV brand and performance advertising budgets, exerting pressure on linear TV and streaming platforms.

- Subscriptions and ARPU expansion:

- With Premium / Music subscribers surpassing 125 million, YouTube has introduced lower-priced tiers such as Premium Lite to further lift overall ARPU.

- AI-driven recommendations and monetization efficiency:

- YouTube’s 15% advertising growth has benefited significantly from increased viewing on Shorts and Living Room platforms, as well as improved content discovery enabled by recommendation systems and Gemini models;

- AI primarily enhances recommendation precision, click-through rates, retention, and creator productivity, amplifying watch time and advertising eCPM.

- Competitive landscape:

- Versus long-form video and streaming platforms (Netflix, Disney+, etc.): YouTube has become the largest video streaming platform by watch time in the U.S., operating a capital-light model centered on UGC and advertising, supplemented by subscriptions, with a more favorable content cost structure than pure-content platforms;

- Versus short-form video platforms (TikTok): each has distinct strengths. TikTok exhibits strong Gen Z engagement, while YouTube counters with Shorts, leveraging its existing creator ecosystem and monetization infrastructure, resulting in faster advertising revenue growth;

- Versus social platforms and TV advertising: Meta Reels and Facebook Watch divert some budgets, but with its integrated long-form, short-form, and TV presence, YouTube has achieved a near-oligopolistic position within the video advertising subsegment;

- Content and regulatory risks: YouTube faces pressures related to content moderation, copyright, children’s privacy, and EU DMA/DSA regulations, though it has not yet become a primary battleground for antitrust litigation.

3.3 Cloud Computing: Google Cloud and the Global Public Cloud Industry

3.3.1 Industry Overview and Competitive Landscape

Cloud infrastructure services have been among the fastest-growing technology markets in recent years:

- In 2024, global enterprise cloud services spending (IaaS, PaaS, and hosted private cloud) reached approximately USD 327–330 billion, with year-over-year growth rebounding to 20–23%;

- In Q3 2025, global enterprise cloud services spending reached USD 107 billion, up USD 7.1 billion quarter over quarter and 27.7% year over year, marking the largest single-quarter increase on record.

The market is highly concentrated among three major players:

- According to Synergy Research Group, AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud collectively account for approximately 62% of global market share, with AWS at around 29% and gradually declining;

- Azure, leveraging Microsoft’s enterprise customer base, holds close to 20% share and continues to gain;

- Google Cloud’s share has gradually increased to approximately 13% in recent years, roughly flat year over year;

- Alibaba Cloud ranks fourth globally with about 4% market share.

The industry exhibits oligopolistic competition:

- AWS leads in scale and product breadth;

- Azure benefits from Office, Windows, and enterprise account integration, with strong positions in large enterprises and government sectors;

- Google Cloud is catching up later, leveraging strengths in AI and big data through large-model APIs, TPUs, and generative AI services.

The cloud market retains significant long-term growth potential:

- Growth above 20% is still expected in 2025, driven by surging compute demand from AI deployment (GPU-as-a-service revenue is growing at over 200% annually);

- Competition is intensifying, with “new cloud challengers” (CoreWeave, Oracle, Databricks, and Chinese vendors) rapidly gaining share in specific niches.

3.3.2 Business Positioning and Structural Role

Google Cloud primarily consists of two components:

- Google Cloud Platform (GCP): IaaS / PaaS (compute, storage, databases, networking), data analytics (BigQuery), AI infrastructure (TPU/GPU clusters), and generative AI platforms (Vertex AI, Gemini models and APIs);

- SaaS: Google Workspace, including Gmail, Docs, and Meet.

At the group level:

- In 2025 Q3, Google Cloud generated USD 15.2 billion in revenue, up 34% year over year, accounting for approximately 15% of Alphabet’s total revenue (up from roughly 12–13% a year earlier), and is widely regarded as the next major growth engine after search advertising.

Strategically, Cloud serves both as the primary commercialization platform for Alphabet’s AI capabilities and as a key pillar for mitigating advertising-related regulatory risks and improving revenue mix quality.

3.3.3 Latest Quarterly Metrics and Profitability

Revenue and growth:

- In 2025 Q3, Cloud revenue reached USD 15.2 billion, up 34% year over year, the fastest growth among Alphabet’s three major segments. In Q3 2024, revenue was USD 11.4 billion, growing 35% year over year; growth remains above 30% despite a higher base;

- Full-year 2025 trajectory:

- Q1: USD 12.3 billion, +28% year over year;

- Q2: USD 13.6 billion, +32%;

- Q3: USD 15.2 billion, +34%.

Profitability:

- In 2025 Q3, Google Cloud operating income reached USD 3.59 billion, up 85% year over year (USD 1.94 billion in the prior-year period), with operating margin expanding to 23%, compared with approximately 17% in Q3 2024—an improvement of about 6 percentage points in one year;

- Achieving rapid margin expansion amid sharply rising AI and data center capital expenditures demonstrates strong operating leverage.

Contribution to group profits:

- Alphabet’s consolidated operating income in 2025 Q3 was USD 31.2 billion, of which Cloud contributed approximately USD 3.6 billion, close to 12%, up from single digits a year earlier;

- By comparison, AWS reported operating income of USD 11.4 billion and Microsoft Intelligent Cloud USD 13.4 billion in the same period. While Google Cloud still lags in absolute profit scale, its profit growth (+85%) significantly outpaced AWS (+10%) and Microsoft (+27%).

Cloud has transitioned from a historically loss-making segment to a mature business characterized by high revenue growth and high profit elasticity, with rapidly rising importance in Alphabet’s earnings structure.

3.3.4 Medium-Term Growth Drivers and Competitive Dynamics

- AI as the primary growth driver:

- Management has stated that Q3 Cloud revenue growth was primarily driven by AI infrastructure and generative AI solutions, particularly Gemini-based model APIs, Vertex AI, and AI-optimized compute;

- Third-party reports indicate that AI-related revenue has reached “multi-billion-dollar” quarterly scale, with its share of Cloud revenue rising rapidly;

- Q3 Cloud backlog reached USD 155 billion, up sharply quarter over quarter, with approximately half expected to convert into revenue within the next two years, providing strong revenue visibility even without new customer additions.

- Continued improvement in profitability quality:

- Cloud margins have risen from 17% to 23–24%. Against the backdrop of Alphabet raising capital expenditure guidance to USD 91–93 billion (primarily for AI and cloud infrastructure), this reflects significantly improved unit economics for compute and storage under high-value AI workloads;

- Fixed-cost leverage effects are increasingly evident.

- Upgrading customer mix:

- Customers are shifting from long-tail SaaS and enterprise experimentation to large enterprises, AI labs, and industry leaders;

- AI labs and traditional large enterprises now coexist as core customers, improving order quality and customer stickiness.

- Competitive landscape:

- Within the three-hyperscaler structure, Google Cloud ranks third by scale but first by growth, steadily gaining share from smaller cloud providers;

- Relative to AWS and Azure:

- Weaknesses lie in traditional enterprise ERP, industry cloud solutions, and channel depth;

- Strengths lie in data analytics (BigQuery), AI/ML (Vertex AI, Gemini), Kubernetes, and high-performance computing (TPU).

- “New cloud challengers” such as CoreWeave, Oracle, Databricks, and certain regional providers pose localized challenges to the hyperscalers in AI, data, and localization-compliance scenarios.

3.4 Subscriptions, Platforms and Consumer Hardware

3.4.1 Industry and Ecosystem Background (Operating Systems and Hardware)

Alphabet’s footprint in hardware and operating systems includes:

- Android mobile ecosystem, the Pixel smartphone lineup, Wear OS smartwatches, Chromebooks, and Nest smart home products.

From an industry perspective:

- Android accounts for roughly 71% of the global mobile operating system market share (vs. ~28% for iOS), holding a clearly dominant position. While Android itself does not directly generate revenue for Alphabet, most handset manufacturers adopting Android are required to pre-install Google’s ecosystem products and set Google as the default search engine. As a result, Android has become Google’s primary traffic source and product distribution gateway in the mobile market.

- However, Alphabet’s influence in branded consumer hardware remains relatively limited:

- Global annual smartphone shipments are around 1.2–1.3 billion units, while Pixel phones account for less than 2% of global volume, with a meaningful presence concentrated mainly in North America and Japan.

- The global smartphone market is led by Samsung and Apple (combined share exceeding 50%), with other Android OEMs such as Xiaomi, OPPO, and vivo dividing the remainder.

- The smart hardware industry overall is highly competitive and structurally low-margin, but it holds distinct strategic significance for Alphabet:

- Hardware helps Google complete the “cloud–device” ecosystem loop and explore a vertically integrated model similar to Apple’s;

- It also ensures that the Android platform is not overly dependent on third-party manufacturers.

In terms of revenue structure:

- In 2024, the “Subscriptions, Platforms and Devices” (SPD) category generated USD 40.34 billion, accounting for approximately 11.5% of total company revenue. This category includes Google Play revenue share, hardware sales, and subscriptions such as YouTube and cloud services.

3.4.2 Business Positioning and Structural Role (SPD)

The hardware and platform segment consists of three components:

- Consumer Subscriptions: YouTube TV, YouTube Music & Premium, NFL Sunday Ticket, Google One, etc.;

- Platforms: Google Play app distribution and in-app purchase revenue share;

- Devices: Pixel devices (phones, tablets), Pixel Watch, Pixel Buds, and smart home / streaming hardware such as Nest and Chromecast.

Within Google Services, SPD is the second-largest non-advertising revenue source, serving several key functions:

- Providing sticky, predictable subscription revenue to improve overall revenue stability;

- Monetizing mobile traffic and the developer ecosystem via Google Play and Android.

- Using Pixel and Nest hardware as “AI endpoints and reference devices” to showcase Gemini’s on-device capabilities and strengthen user lock-in to the Google ecosystem.

3.4.3 Latest Quarterly Performance and Profit Contribution

Revenue and growth:

- In 2025 Q3, Alphabet reported total revenue of USD 102.35 billion, up 16% YoY;

- SPD revenue reached USD 12.87 billion, up 20.8% YoY from USD 10.66 billion in 2024 Q3.

In rough terms:

- SPD accounts for approximately 12–13% of Alphabet’s total revenue.

- And around 15% of Google Services revenue.

Profit contribution (qualitative):

- Alphabet does not disclose SPD margins separately, but:

- Subscriptions (YouTube Premium/TV, Google One) and Play revenue share are high-margin digital services, while hardware margins are lower and often near breakeven.

- Based on 10-K disclosures stating that SPD growth is “primarily driven by subscription revenue, particularly YouTube services and Google One,” it is reasonable to conclude that:

- Overall SPD margins are mid-to-upper range within Google Services, slightly below pure advertising;

- The primary profit contributors are subscriptions and platforms, while hardware plays a more strategic and branding-oriented role.

From a trend perspective, SPD revenue grew from USD 34.69 billion in 2023 to USD 40.34 billion in 2024, an increase of USD 5.7 billion (+16.4%), clearly driven by subscriptions. In 2025 Q3, quarterly growth further accelerated to around 21%, indicating that this segment is increasingly amplifying its contribution to group profitability.

3.4.4 Mid-Term Growth Drivers and Competitive Landscape

- Subscriptions: YouTube and Google One as core growth engines

- YouTube Music & Premium surpassed 125 million paid users (including trials) as of March 2025;

- YouTube TV exceeded 8 million subscribers, with premium sports rights such as NFL Sunday Ticket driving high ARPU;

- Google One continues to grow steadily as a bundled cloud storage and value-added service, and was explicitly cited by the CFO as the second-largest contributor to SPD growth.

Both management commentary and 10-K disclosures suggest that the “cash cow” within SPD has shifted from early reliance on Play to high-margin, recurring subscription revenue from YouTube services and Google One.

- Platforms: Google Play in a mature, cash-generating phase

- Android’s roughly 70% global OS share provides a stable transaction base for Google Play.

- Although not officially disclosed, industry estimates place annual user spending at USD 55–60 billion, implying Play revenue of roughly USD 6–9 billion per year. Growth is slower than subscriptions, but margins remain high.

- Mid- to long-term risks stem mainly from regulatory pressure in the EU and U.S. regarding commission rates, bundling requirements, and third-party payment options.

- Hardware: Pixel and others as strategic and branding assets

- Pixel remains a niche brand globally, with low single-digit market share; in the U.S., following the launch of Pixel 10, share has increased from roughly 2–3% to 3–4%.

- The gap versus Apple and Samsung remains wide, with competition focused on AI photography, native Android update speed, and deep integration with Google services.

- Pixel Watch, Pixel Buds, and Nest products benchmark against Apple Watch, AirPods, and Amazon Echo & Ring, primarily serving as data entry points and experience showcases;

- Management has stated that smartphones will remain the central consumer device over the next 2–3 years, with AI hardware such as smart glasses not yet ready to replace them.

3.5 Autonomous Driving and Waymo: The Mobility Technology Frontier

3.5.1 Industry Overview and Technology Approaches

The global robotaxi industry remains at an early stage, but is transitioning from “capital-intensive R&D” toward “territorial expansion”:

- The current market size is still small (annual revenue under USD 1 billion), but many forecasts project a 50–70% CAGR between 2025 and 2030;

- 2024–2025 is widely viewed as an inflection period, with cities such as San Francisco, Phoenix, and Los Angeles opening commercial routes, shifting robotaxi from “tech experiments” to regional operations.

Technology and commercialization paths broadly fall into three categories:

- Asset-heavy / full-stack approach (LiDAR + HD maps)

- Representatives: Waymo (Google), Zoox (Amazon), Cruise (GM);

- Multi-sensor fusion, HD maps, and rule-based + AI hybrid systems deliver strong safety performance in complex environments, but vehicle modification costs are high.

- Pure vision / end-to-end approach

- Representatives: Tesla Cybercab, etc.;

- Camera-based, end-to-end neural networks offer lower costs and better generalization, but suffer from explainability issues and face stricter regulatory scrutiny.

- “China model” with vehicle–road–cloud integration

- Representatives: Baidu Apollo, Pony.ai, WeRide;

- Leverages roadside infrastructure, V2X, and policy support to scale rapidly in select cities, with strong cost control and earlier breakeven potential.

Despite progress, the industry still faces technical bottlenecks (long-tail scenarios, safety reliability) and regulatory uncertainty. Several robotaxi incidents in 2025 reignited regulatory tightening discussions, indicating that full-scale commercialization will take time.

3.5.2 Waymo’s Positioning and Latest Developments

Waymo is Alphabet’s L4 autonomous driving subsidiary, originating from the Google self-driving car project launched in 2009. Its focus areas include:

- Consumer robotaxi services (Waymo One);

- Potential future freight and enterprise mobility solutions.

Financially, Waymo is grouped under Other Bets alongside Verily, Calico, and X:

- In 2024, Other Bets generated USD 1.648 billion in revenue with an operating loss of USD 4.444 billion;

- Revenue for the first nine months of 2025 was USD 1.167 billion, slightly down YoY.

- Waymo is widely viewed as the largest and most commercially promising Other Bet, but remains positioned as high investment, early revenue, long-duration optionality.

Operational scale and expansion:

- City coverage: Commercial robotaxi services in Phoenix, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Austin, Atlanta, and others;

- Fleet size: Approximately 2,500 vehicles in operation as of November 2025, primarily modified Jaguar I-PACE models;

- Driving and rides: Over 100 million autonomous miles driven on public roads; As of February 2025, over 200,000 rides per week, with cumulative paid rides exceeding 10 million by mid-2025.

Latest expansion:

- In November 2025, California expanded Waymo’s driverless permit, allowing operations across a much larger Bay Area and Southern California footprint, covering approximately 47,493 square miles.

- Approval to operate on major highways (101, 280) and airport routes significantly expanded the urban network.

- The sixth-generation hardware platform (Waymo Driver Gen 6) upgraded sensors and compute while materially reducing costs, laying the foundation for larger-scale deployment.

3.5.3 Financial Contribution and Mid-Term Trends

Alphabet does not disclose Waymo revenue separately, only aggregate Other Bets figures:

- 2024 Other Bets revenue: USD 1.648 billion, operating loss USD 4.444 billion;

- 2024 Q4: quarterly revenue around USD 400 million, operating loss USD 1.2 billion;

- Third-party estimates suggest Waymo generated approximately USD 125 million in ride-hailing revenue in 2024, potentially exceeding USD 1.3 billion by 2027.

Between 2023 and 2025, Other Bets’ annual operating losses remained around USD 4 billion, while revenue stayed in the low single-digit billions. Given Waymo’s long investment cycle, capital intensity, and still-limited commercialization, the market generally views Waymo as one of the primary sources of losses within Other Bets, exerting a persistent drag on Alphabet’s consolidated profits.

Estimated operating trajectory (third-party):

- Rider-only vehicle miles traveled: ~8 million (2023) → 40.8 million (2024) → ~324 million (2027), implying near-100% CAGR;

- Annual paid rides: ~5.69 million (2024) → ~15.4 million (2025E) → ~48 million (2027E);

- Revenue: ~USD 125 million (2024) → potentially over USD 1.3 billion (2027).

While estimated, these figures indicate a pattern of small bases, steep growth, transitioning from pilot programs to regional operations.

Capital and cost dynamics:

- Total external funding of approximately USD 11.1 billion between 2020 and 2024, including a USD 5.6 billion round in October 2024 at a post-money valuation exceeding USD 45 billion;

- Gen 6 hardware materially lowers per-vehicle costs, but the model remains asset-heavy and operationally intensive;

- Mid-term focus lies on whether declining hardware costs, higher vehicle utilization, and city-level replication can gradually improve unit economics.

3.5.4 Competitive Landscape, Moats and Risks

U.S. market:

- Waymo leads in a number of cities, fully driverless miles, and paid trips;

- GM’s Cruise has seen licenses suspended following accidents, limiting the near-term threat.

- Zoox operates free trial programs in Las Vegas and elsewhere, but remains smaller in scale.

- Tesla plans to launch Cybercab in 2026. Its pure-vision approach and regulatory feasibility remain debated, but it represents Waymo’s primary long-term challenger.

China and other regions:

- Baidu Apollo Go operates robotaxi services in over ten cities, including Wuhan, Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen. In 2025 Q1, quarterly orders exceeded 1.4 million, roughly 50–60% of Waymo’s volume;

- Institutions project robotaxi software revenue could grow by multiples over the next 20 years, though the current global market remains under USD 1 billion.

Waymo’s moats:

- Technology and data accumulation: over 100 million autonomous miles, massive simulation datasets, and rider-only VMT form algorithmic and safety advantages;

- Integrated hardware–software design with proprietary sensors and compute platforms enables long-term cost optimization;

- Synergies with Alphabet’s ecosystem: maps, AI, and cloud infrastructure provide compute and data support.

Key risks:

- Unit economics remain unproven, with skepticism over whether tens of billions in investment can be recouped via operations in a limited number of cities.

- Safety and public perception risk: serious accidents could trigger license freezes and slow expansion.

- Policy and social acceptance: concerns around traffic safety, employment, and privacy may constrain scaling speed.

3.6 The Artificial Intelligence Industry and Alphabet’s AI Business Lines

Before analyzing the AI industry and Alphabet’s “AI business lines,” it is necessary first to define what we mean by the “AI industry” and how it is structured.

3.6.1 Global AI Industry Structure and Evolution

- Industry Composition and Market Size Breakdown

The AI industry exhibits a structure characterized by heavy infrastructure investment with rapidly emerging applications, and can be divided into three layers: Infrastructure, Models & Platforms, and Applications & Services.

Infrastructure Layer (approximately 45–50%, USD 135–150 billion):

- Computing chips: GPUs (NVIDIA Blackwell/Rubin), various ASICs (e.g., Google’s TPU);

- Servers and networking: High-density AI servers, high-bandwidth memory, optical interconnects;

- Energy and data centers: Liquid-cooled data centers redesigned for AI workloads.

Characteristics: Currently, the segment with the strongest cash flows and highest certainty. Training demand remains robust, while inference-related compute spending already accounts for more than 40% of total demand and continues to rise.

Models & Platforms Layer (approximately 20–25%, USD 60–75 billion):

- Foundation models: OpenAI, Google Gemini, Anthropic Claude, Meta Llama, etc.;

- MLOps and toolchains: Vector databases, data labeling, model hosting platforms;

- Cloud AI incremental services: Azure AI, Google Cloud Vertex AI, AWS Bedrock, etc.

Characteristics: Intense API price competition. Prices for general-purpose model API calls have fallen by roughly 80% year-over-year. The impact of open-source models is significant, and the layer is showing a clear trend toward commoditization.

Applications & Services Layer (approximately 30%, ~USD 90 billion):

- Enterprise applications: Agent-embedded CRM, office suites, code assistants;

- Consumer applications: Search, companion apps, creative tools;

- Vertical solutions: AI drug discovery, legal contract review, financial risk control, etc.

Characteristics: The fastest-growing segment. AI has moved beyond “tech toys” into real commercialization, with enterprises increasingly willing to pay for “agents that actually get work done.”

- Growth: From Explosion to the Deep-Water Phase

- Overall growth: Maintained at 26–30% during 2024–2025;

- By layer: Application layer growth >35% (third-party estimates), infrastructure ~25%, model layer ~20%, corresponding respectively to explosive, maturing, and early-saturation phases;

- Business model evolution: From “per-seat SaaS pricing” to “pay-per-outcome” models. Typical examples include Intercom, Salesforce Agentforce, Sierra, Adobe Firefly, and Waymo. By significantly reducing labor costs and charging based on service delivery, AI adoption across industries is accelerating rapidly.

- The “Seemingly Unprofitable” Paradox of the Model Layer and Its Structural Opportunities

Despite declining per-token revenues due to API price cuts, open-source competition, and price wars, leading platforms can still generate value by:

- Leveraging scale effects and technological progress to reduce unit costs;

- Increasing ARPU through PaaS/SaaS bundling and Agent/Workflow-based pricing;

- Locking in long-term pricing power through cloud infrastructure and developer ecosystems.

The most likely future market structure is: a small number of dominant model platforms, plus a group of profitable vertical-industry model solution providers, while a large number of low-differentiation general-purpose models gradually exit the market.

- Four Major Trends from 2026–2030

- From Chat to Action: The full arrival of the Agent era, where AI directly “does the work,” further promotes outcome-based pricing and reduces the share of labor costs in enterprise expense structures.

- From Cloud-Centric to Edge–Cloud Collaboration: The explosion of on-device AI, with smartphones and PCs becoming edge computing hubs, driving replacement cycles for AI PCs and AI smartphones.

- From Training Compute to Inference Compute: Electricity and energy become new bottlenecks. New energy infrastructure, such as SMRs (Small Modular Reactors), emerges as a critical investment theme.

- The Rise of “Sovereign AI”: Comprehensive AI capability becomes a core national strategic asset. Governments and sovereign wealth funds significantly increase investment in domestic models and compute infrastructure.

Overall, the AI industry is at a turning point where infrastructure is largely in place and applications are beginning to commercialize:

- The infrastructure layer remains a cash cow, but its most aggressive expansion phase is over;

- The application layer will be the main battlefield for the next generation of trillion-dollar companies after 2026.

- The models and platforms layer is evolving into a new form of infrastructure—high-investment, high-scale-efficiency—where the vast majority of profits will be captured by a small number of dominant players.

3.6.2 Assessment of the AI Bubble

Before assessing the “AI bubble,” we must first answer two questions:

- What is an AI bubble?

- How would the severity of an AI bubble affect our evaluation of Alphabet?

After clarifying these, we can then address the key issues:

- What is the current degree of the AI bubble?

- How does this level of bubble actually affect Alphabet’s valuation and future?

What Is an AI Bubble?

An AI bubble refers to a situation in which expectations, stock prices, and capital investment surrounding artificial intelligence are significantly overestimated relative to the cash flows and productivity gains that can realistically be generated in the foreseeable future.

Proponents of the “bubble” view argue that the value creation and efficiency improvements brought by AI are far lower than current market expectations suggest. As a result, massive infrastructure investments driven by these inflated expectations—including chip procurement and data center construction—may ultimately face insufficient real demand. This would lead to substantial write-downs in equipment and fixed assets, directly eroding corporate profits. In addition, companies across the AI value chain would be forced to significantly revise downward their revenue and operating profit growth expectations, resulting in sharp valuation compression.

The non-bubble camp holds the opposite view or adopts a more neutral and balanced stance.

Direct Impact of an AI Bubble on Alphabet

Alphabet’s core investment narrative today can essentially be summarized in three points:

- The advertising engine remains highly efficient (Search + YouTube).

- Cloud is scaling up and turning profitable, driven by AI demand.

- AI (Gemini + TPU + Vertex + AI-powered Search) is the core driver of the next growth phase and competitive moat.

If we believe AI is in a severe bubble phase, then the second and third pillars of this narrative are at risk of breaking:

- Cloud AI demand is overestimated, requiring downward revisions to growth and profitability expectations for GCP, TPU, and Vertex AI.

- Large-scale AI capital expenditures may translate into fixed assets that face value impairment and accelerated depreciation, leading to a rapid decline in net profits.

Debating the AI Bubble: Key Arguments From the Bull and Bear Sides

Main Arguments of the “AI Bubble” Thesis:

- Extreme valuations and concentration, with stock market gains heavily dependent on a small number of AI leaders. Technology companies highly correlated with AI already account for approximately 44% of the S&P 500’s total market capitalization, and contributed roughly two-thirds of the index’s gains in 2025, a pattern similar to the internet bubble from the 1990s to 2000.

- Capital expenditures are far ahead of actual demand, leading to excessive infrastructure build-out. Global AI-related investment over the next five years could exceed USD 5 trillion. Alphabet alone is expected to spend close to USD 100 billion in capital expenditures this year, while downstream demand expansion remains slow, meaning investment levels are far greater than the revenues that can realistically be generated in the future.

- Suspected financial manipulation: circular revenue inflation and overly optimistic depreciation assumptions. Across the ecosystem, there are cases of “vendor financing,” where upstream suppliers provide financing to downstream customers, who then use those funds to purchase the suppliers’ own products. A representative example is NVIDIA’s equity investments in OpenAI and CoreWeave, after which the latter purchased GPUs from NVIDIA. In this scenario, NVIDIA obtains both orders (recognized as revenue) and equity stakes in the investee companies on its balance sheet. Financial statements, therefore, look very strong in the short term. However, if downstream AI demand fails to keep up and these companies encounter operational difficulties, not only will future orders contract, but the value of the equity stakes will also decline and require write-downs. In addition, most leading cloud providers such as Microsoft, Google, and Amazon generally adopt five- to six-year depreciation periods for equipment. However, due to rapid product iteration, GPUs and similar chips only have a peak performance window of roughly three years, after which they are typically used for lower-complexity tasks. Prominent Wall Street short seller Michael Burry argues that this accounting treatment understates annual depreciation in the short term, overstates corporate net income, and constitutes a form of financial misrepresentation.

Conversely, the main arguments for why the current bubble is limited or reasonable are:

- The profits and cash flows of current AI leaders are real, not the “zero-profit, story-driven valuations” seen in 2000. Representative AI companies today—whether upstream chip designers such as NVIDIA, manufacturers such as TSMC, or midstream cloud platform giants such as Google, Amazon, and Microsoft—all possess strong profitability and cash flow generation. This differs fundamentally from internet companies during the bubble era, many of which were not yet profitable and relied primarily on external financing. If we look only at P/E multiples, the forward one-year P/E ratios of today’s leading companies are generally in the 30–40x range or lower. While these levels are above historical averages, they are far more reasonable than those seen during the dot-com bubble. More importantly, aside from NVIDIA, the majority of revenue and profit for large companies such as Google, Microsoft, and Amazon still come primarily from their traditional core businesses (although the contribution of AI-related businesses is rising rapidly). Even if the AI investment thesis were to be completely invalidated (which is highly unlikely), these companies would still have strong core business foundations supporting their market capitalizations. As a result, it is difficult to envision a repeat of the 2000 tech bubble collapse, when many companies saw declines of 70% or even 90%.

- Technology and demand are real and observable, and AI is already delivering visible productivity gains and revenue. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella has recently stated clearly that revenue growth at Azure, driven by AI, has approached or exceeded 40%. Similar statements have been confirmed by Meta and Google. Major Chinese technology companies such as Tencent and Alibaba have also made similar remarks in their earnings reports and investor calls over the past year, noting that AI has directly or indirectly improved the profitability and efficiency of their core businesses. If AI-driven efficiency improvements at large companies could still be dismissed as isolated cases, another category of data more convincingly demonstrates the reality of rapidly growing AI demand: AI-related services (including compute capacity) offered by major cloud providers are in a state of undersupply. Flagship chips are running at full utilization, and even older GPU models remain in active service. For example, during the Q3 2025 earnings call, Alphabet’s management explicitly stated that Google Cloud’s remaining performance obligations (RPO) reached USD 155 billion, up 46% quarter-over-quarter and 82% year-over-year, and emphasized that “this growth is primarily driven by AI demand.” In the same month, during Alibaba’s earnings call, CEO Eddie Wu Yongming stated that “the pace at which Alibaba Cloud can bring AI servers online is seriously lagging the growth of customer orders, and the backlog of outstanding orders continues to expand, with future potential still accelerating.” If NVIDIA’s optimism about AI could be dismissed as “talking its own book,” then the fact that downstream enterprise customers are spending real money on AI cloud resources provides even stronger evidence of the current reality of the AI industry—demand is real and growing rapidly, and is currently concentrated primarily on the enterprise side.